With Both Hands, And…

![]() A map is a very handy thing for a writer. It can help you gauge how long someone’s journey would take, or remind you of the river between points A and B. If you’re using a real-world locale, then you’ll want to keep your depiction in line with reality. If your locale is your own invention, then you’ll want to keep your depiction internally consistent.

A map is a very handy thing for a writer. It can help you gauge how long someone’s journey would take, or remind you of the river between points A and B. If you’re using a real-world locale, then you’ll want to keep your depiction in line with reality. If your locale is your own invention, then you’ll want to keep your depiction internally consistent.

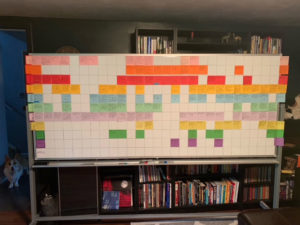

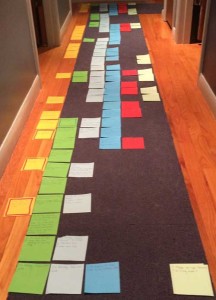

Way back at the start of things for As-Yet-Untitled Ghost Novel #1, we created a map of the main setting, which is a place we made up. Over the course of actually writing that book, we annotated the map with a great many pencil marks showing adjustments and additions. It’s become sort of a mess.

So, as part of our preparations for diving into prose on As-Yet-Untitled Ghost Novel #2, Kent is updating the map so we have a clean version to work from. The more we write about the place, the more we learn about it ourselves, so we assume we’ll need to do more map updates when we get to books 3 and 4 as well.

A writing partner is someone who helps you keep your bearings.