The Skelley Fiction Roadmap

![]()

We mention stubs a lot, but it’s important to understand that we don’t just pull them out of thin air. The process has steps that go in a certain order, becoming more detailed as they progress.

Our first major step is a rainbow, which is how we collate the random notes from one or more steno pads we fill up during our brainstorming sessions. (So, those steno notes are prolly our real first step. But you know how to write in a notepad, we think.)

The rainbow is a color-coded representation of the major story beats. Each square of paper is approximately equal to a scene.

(Details about how we build and use the rainbow can be found here.)

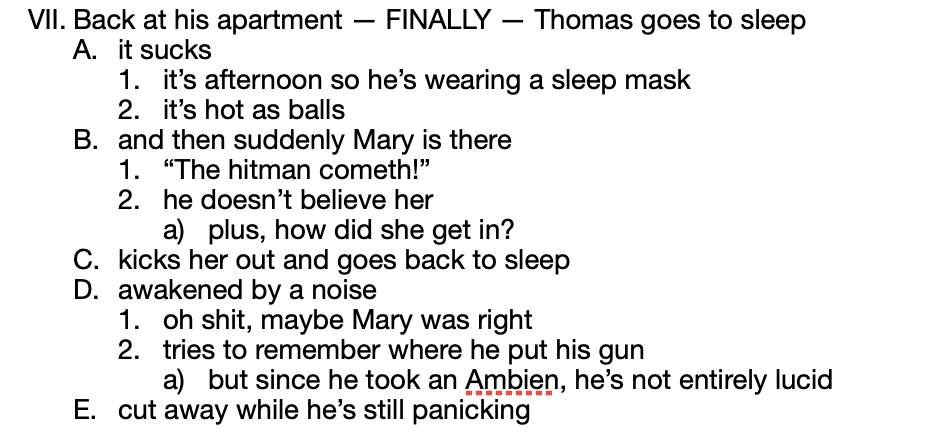

The rainbow gets turned into an outline, which doesn’t follow the strict formatting you learned in school. If we were to write a hitman novel, it would look something like this:

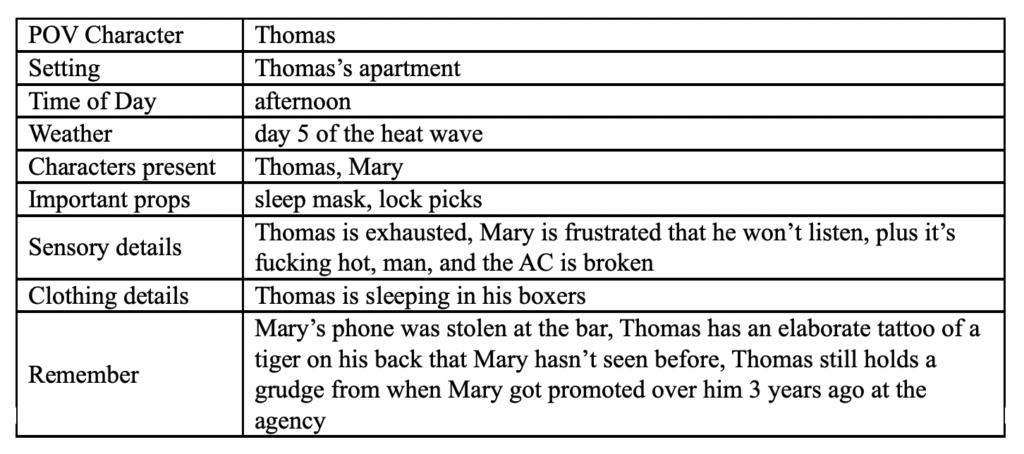

And that gets turned into a stub. We fill in the template and write a scene synopsis like so:

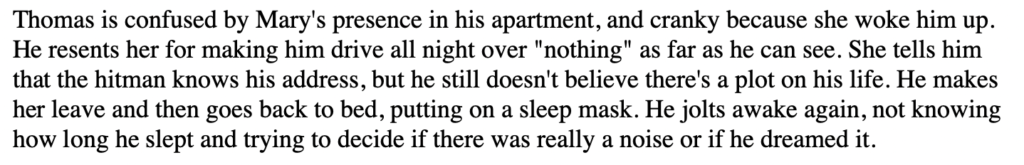

The meat of the stub is the scene synopsis: a page or so of text that lists all the major events and how they make characters feel. (Our real stubs are generally longer than the above example.) The stub is not the scene; it’s the instructions for building it. The stub is allowed to tell instead of showing, in fact it’s encouraged. Don’t get fancy here.

When the actual scene gets written based on this, phrases like “Thomas is confused” would be replaced along the lines of, “He stared at Mary, whatever she was saying drowned out by a litany of objections to her very presence. She didn’t have a key, for one thing. He’d never told her his address, for another. And she fucking well knew she’d be waking him up.” (Snuck a little “… and cranky” in there too.)

We find the word count goes up by a factor of at least four, sometimes more like ten, when progressing from stub to scene. Any salient info that isn’t actually in the scene should still be noted in the stub. This is what we usually use the “Remember” line for in the template. If Mary hasn’t eaten in two days, mention that. Even if she’s not the POV character.

What to leave out of the stub: description, mainly. Mention only the specific details that are key to the scene’s meaning and mission.