Kent and Jen spent most of the evening revising a query letter, by literally passing the keyboard back and forth. It’s not the normal Rune Skelley process, but with something as brief as a letter it made sense. It was exhausting!

Kent and Jen spent most of the evening revising a query letter, by literally passing the keyboard back and forth. It’s not the normal Rune Skelley process, but with something as brief as a letter it made sense. It was exhausting!

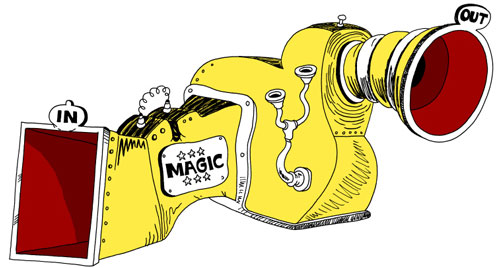

That’s probably the image that a lot people form when they hear that we write together. Maybe some co-authors do work that way all the time, but it seems doubtful. When we’re working on a novel we go through distinct stages, and how we collaborate changes depending which stage we’re in.

The initial conceptualization and outlining are intensely collaborative and real-time. Much of it happens out loud, with one of us charged with taking notes.

After that comes the creation of stubs. Jen does 99% of the stubbing, but as soon as there are a few of them in the bag Kent can get started on the first-draft prose. So in this phase of the project, we’re working in the same room at the same time, on the same novel, but we’re tackling separate aspects of it in parallel. It’s a divide-and-conquer approach.

Once stubbing reaches a certain point, Jen joins in on the prosification. She and Kent choose which scenes to work on based on which characters and subject matter they feel the greatest affinity for, and sometimes there’s a little arm wrestling involved.

Eventually, all these isolated scenes written by different people need to come together into a harmonious whole. Smoothing the seams and debugging the story flow is the bulk of the work involved with our second draft. This marks a return to a more simultaneous work style, discussing the moves as we make them. There will often be rewriting or entire new scenes that we discover a need for, so there’s also some parallel work going on.

Somewhere in here is when we begin taking chapters in for our critique group. Gathering and analyzing the feedback is another intensive aspect of collaboration. We’re both there, and we trade knowing glances as readers speculate about plot twists. We pore over the marked-up copies we get back, and collate the input that we plan to factor into the next revision pass.

While the manuscript is “rough” we tend toward the parallel approach, splitting up the scenes between us and putting more polish on things each time through until it’s time to shift gears again. In the finishing stage, we pull up our chairs to the same desk and go through the whole book together. It looks a lot like how we worked on the letter tonight, but that resemblance is superficial. We have a highly developed system for those late-stage edits on our novels. What made the letter so much more tiring was that we were composing it as much as revising it. Rather than just needing to agree on whether or not we need the word “had” in a sentence, we needed to create cogent sentences out of thin air.

![]() Rune Skelley’s habitat has been a rather hectic place of late. In addition to the recent travel and interviews that we mentioned the past couple of Fridays:

Rune Skelley’s habitat has been a rather hectic place of late. In addition to the recent travel and interviews that we mentioned the past couple of Fridays: