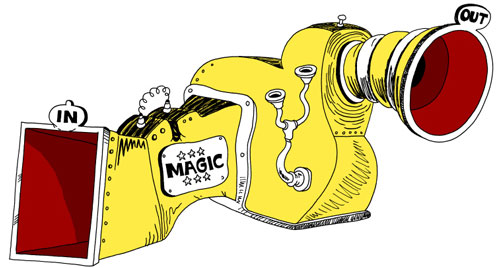

Readers want to feel immersed, and they want to place their trust in the author to know where the story is going. These concepts shake hands through the magic of world-building: in order to help people forget that everything on the page is made up, you must make up a ton of additional stuff to give it context.

Readers want to feel immersed, and they want to place their trust in the author to know where the story is going. These concepts shake hands through the magic of world-building: in order to help people forget that everything on the page is made up, you must make up a ton of additional stuff to give it context.

Despite the oft-touted genre influence on how much world-building is called for, the simple fact is that all narrative — nonfiction included — needs to create a compelling environment, a vivid arena where the action will unfold. And it needs to be expansive enough to feel unbounded, like the story could go in any direction and never hit a trompe-l’oeil backdrop. In a realistic story this might not, technically, count as world-building, but let’s not get hung up on technicalities. Whether it’s a beach in the Caribbean or a plateau on Mars, you want your reader to feel the sand.

This is sometimes described as the sense that the story extends past the edges of the page. Striving for that effect raises an important question: how far?

World-building is a type of research. You’re just creating information rather than finding it in other sources. As with all forms of research, there’s a risk of falling down a rabbit-hole. Erring on the side of thoroughness is probably wise, but stay wary of the point of diminishing returns. Questions that come up in the middle of writing a scene can derail your productivity if you fixate on them.

In Son of Music Novel, one of the secondary characters is on television, in a show we made up. We know what it’s called, but up until a recent work session we hadn’t filled in anything else about it. And, the show’s title suggested two possible kinds of show it might be. We know that the show needn’t be depicted on the page, so theoretically we don’t need to settle the question of what it’s about.

But we do, actually. Tossing off a title that’s not attached to anything calls attention to the gap. It makes a reader wonder. Wondering what’s behind that title turns into wondering if the author’s ever going to address it, reminds the reader that someone made all this up.

What we (probably) won’t do is make lists of episode titles. The band’s discography is documented in tremendous detail, but there’s a reason we call this book’s parent the Music Novel. It’s not the Television Novel. You need to prioritize, because the world you’re building truly is boundless. This is where it can be helpful to have someone (a writing partner, for instance) who can act as a sounding board and help you know when it’s time to climb out of the rabbit-hole.

![]() The frustrations of sending query letters do sometimes have their compensations, such as when an agent asks for a full. That happened to us this week, which (a) makes us both extremely happy, and (b) feels a little spooky considering that just last week we vented about marketing.

The frustrations of sending query letters do sometimes have their compensations, such as when an agent asks for a full. That happened to us this week, which (a) makes us both extremely happy, and (b) feels a little spooky considering that just last week we vented about marketing.