How Would You Describe That?

![]() The heavy lifting is done in our revisions of the Music Novel, aka Novel #4, but we still have miles to go. We’ve set up a list of global revision issues, each of which pretty much necessitates a separate pass through the full manuscript.

The heavy lifting is done in our revisions of the Music Novel, aka Novel #4, but we still have miles to go. We’ve set up a list of global revision issues, each of which pretty much necessitates a separate pass through the full manuscript.

For example, one of the major characters is British, and we identified the need to make that more evident through the usage choices in her scenes. Not just within her dialog, but also the narrative if the scene is from her point of view — we want her point of view to really be the camera lens for those scenes. In other, subtler ways, each POV character needs similar attention. Some of them are less optimistic about life (especially later in the tale…) and some of them are just wired differently. We want certain foibles to be evident in which details the character’s notice, and in their choices of inward adjectives and similes.

And on top of all that, we also need to make the locale more vivid. This one’s set in New York City, primarily Manhattan, and we apparently got lazy about describing the place. After all, it’s on TV a thousand times a week, so everybody knows what it’s like, right? Lazy! Our real wake-up about this issue was when we heard reader feedback on Novel #5, and people repeatedly praised the job we did on the setting. In that case, it’s a fictitious city and because we made it up we were eager to tell folks all about it. So to fix things in the Music Novel, we came up with this simple strategy: pretend we invented New York City. It makes the writing more fun, largely because of the frequency with which we realize just how weird a place New York actually is, probably weirder than anything we would have concocted!

To deal with so many global changes, we split up the list between us. Kent is focusing mainly on “inventing NYC” at the moment, and Jen has moved on from the Anglophonic project to physical traits of the characters. It’s humming along pretty well now, but it’s taken the past week or so for Kent to get back into the swing of things now that we’re back from Europe. Jen must be more resistant to jet lag.

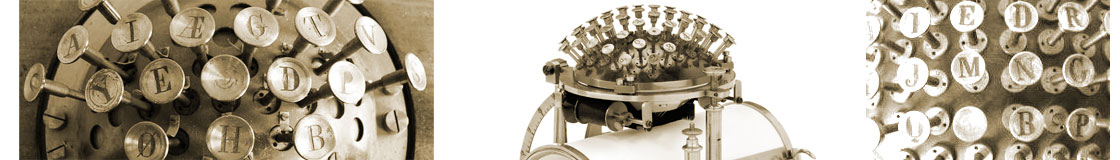

Did we mention we were going to Europe? Prague is a devastatingly gorgeous city. We insist you visit. Go. Right now. Eat trdelník and schnitzel. Drink hot wine and Pilsner Urquell. Visit the astronomical clock and the Museum of Sex Machines. We couldn’t invent a better city if we tried.