Failure to Plan = Planning to Fail

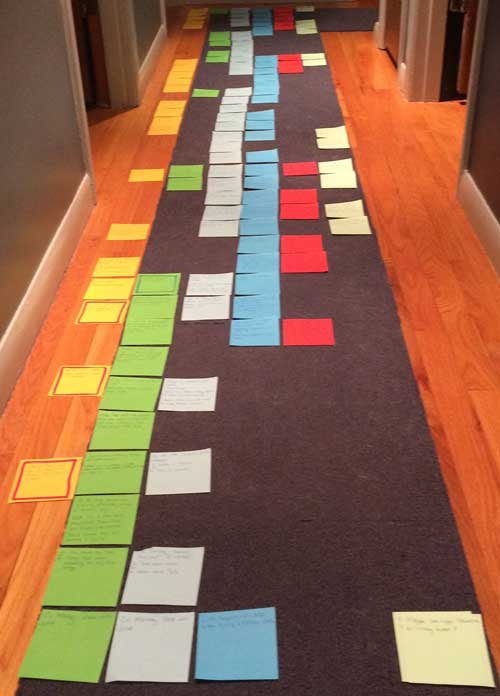

![]() The 8-page synopsis we talked about last week has spawned a bouncing baby outline, a whopping 26 pages long (!). Once you get back up from your fainting couch, let us hasten to explain. This is an incredibly detailed outline, including almost everything we know about the story and its characters.

The 8-page synopsis we talked about last week has spawned a bouncing baby outline, a whopping 26 pages long (!). Once you get back up from your fainting couch, let us hasten to explain. This is an incredibly detailed outline, including almost everything we know about the story and its characters.

Also, this is not an outline that your English teacher would approve of. It does not follow proper outline formatting. There are many instances of sections having a single subheading (an A with no B, for instance). We’re not concerned with getting a good grade on this, we’re concerned with arranging all of our plot knowledge into something like chronological order. Our notes included a lot of backstory, so we had to determine where in the action it made the most sense to introduce that information.

Some writers might feel like so many steps are unnecessary. Why do we need to have extensive notes, plus a Plot Rainbow, plus a multi-page synopsis, PLUS an outline? (And we haven’t even gotten to stubs yet.) Each iteration presents the plot in a different way, and each exposes areas where there are still questions, or where there is magical thinking going on. A solo writer might get away with being a little more seat-of-the-pants, but when you’re working with a writing partner, it’s vital that you both have a clear picture of what’s going on. You both have to agree on how everything is handled, and you have to be able to put your individual pieces together to form a coherent picture. If you’re working from different sets of assumptions, your prose jigsaw will be extremely frustrating indeed.

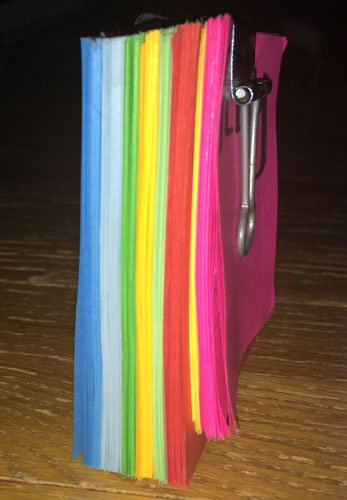

We spent an evening carefully combing through that first Rainbow, making notes about points that were still vague, or questions that were still unanswered. Then we retired to the auxiliary writing cave and filled in all of the missing information.

We spent an evening carefully combing through that first Rainbow, making notes about points that were still vague, or questions that were still unanswered. Then we retired to the auxiliary writing cave and filled in all of the missing information.