Begin Again

![]() Finally! The first draft of Son of Music Novel is officially done. We wrapped up the lingering loose ends a few days ago and tucked it away for safekeeping. As we mentioned a few weeks ago, we prefer to take things to critique group once we’ve sanded off the worst of the imperfections, which means that our new baby is not quite ready for its public debut. It’s all tired and shagged out following a prolonged squawk, and needs a bit of a lie down while we work on other things.

Finally! The first draft of Son of Music Novel is officially done. We wrapped up the lingering loose ends a few days ago and tucked it away for safekeeping. As we mentioned a few weeks ago, we prefer to take things to critique group once we’ve sanded off the worst of the imperfections, which means that our new baby is not quite ready for its public debut. It’s all tired and shagged out following a prolonged squawk, and needs a bit of a lie down while we work on other things.

Picking up a new project (or revisiting an old one) forces us to focus on something different and drives the details of the newly completed novel from our minds. That way, when we pick it up again, we can look at it with fresh eyes. Obviously we’ll never be unspoiled readers of our own work, but one does what one can.

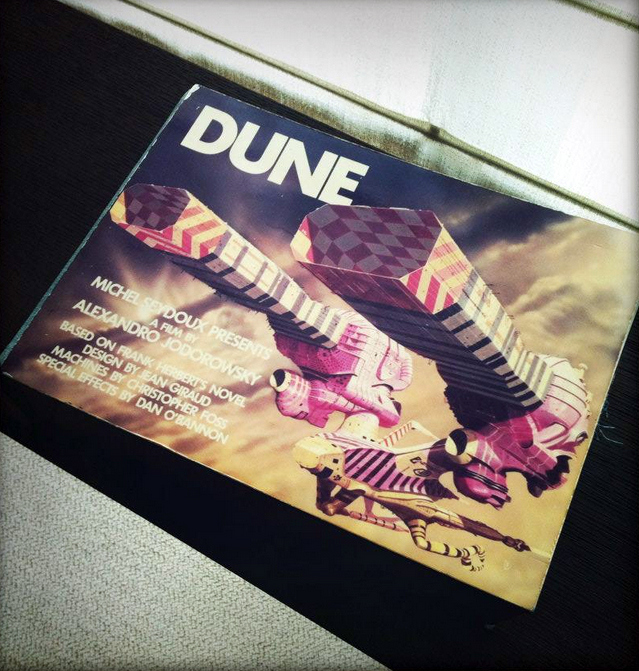

Our new project will be a sequel to Novel #5, which we cleverly code-named the Science Novel. Most likely it will be known here on the blog by the nom de guerre Son of Science Novel, even after we decide on its real title. We dug up some existing notes on potential directions the sequel could take, reminded ourselves which characters survived the first outing, and looked at the pretty pictures of the not-so-pretty locations we’re taking inspiration from for possible settings. It’s been fun and refreshing to shift gears, and we’re looking forward to a deep dive back into the world we created for Science Novel.

That and watching The Man in the High Castle, and seeing Star Wars again.