The Stubulator Has Been Activated

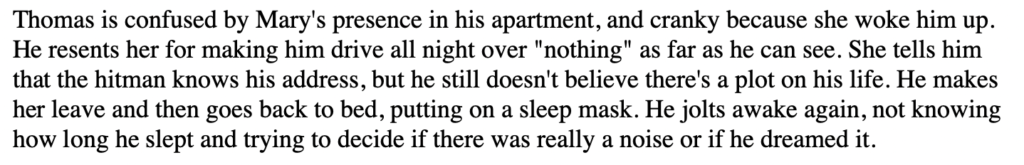

![]() Progress report: Jen has stubbed out the first six scenes for As-Yet-Untitled Ghost Novel #2. Typically we aim to have about a dozen stubs ready before writing any of the actual scenes, so we should reach that stage very soon!

Progress report: Jen has stubbed out the first six scenes for As-Yet-Untitled Ghost Novel #2. Typically we aim to have about a dozen stubs ready before writing any of the actual scenes, so we should reach that stage very soon!

Each phase of our process (brainstorming, rainbowing, the prose outline, the actual outline, the stubs, and then finally actual prose) requires a different kind of writing. And there’s always a little hill to climb when we revisit any of those phases after being away from it for a while, to relearn how to do that kind of writing.

Still, we trust the process. Each of those phases helps us understand our story from another angle, making things go a lot smoother during the prose phase and leading to an overall superior end result.

Also, we’ve learned the hard way that staying in any one phase for too long can lead to burnout. We ended up writing the prose for two entire novels back-to-back once. But only once. It’s nice being able to shift gears, use different muscles now and then. Keeps us sane.

A writing partner is someone who shares your faith in the process.